(Koker, 2016)

The 2002 United States National Security Strategy (NSS) clearly upholds an influence of the events of 9/11 on the stance adopted by US foreign policy under the Bush administration and its ‘consequential’ national objectives on the global war on terror. It is key to analyse the ramifications the US NSS has there forth had on sovereignty and intervention, evoking a changing international system in a post-Cold War unipolar world, challenging the notion of sovereign equality and laws governing the use of force (heretofore Westphalian order) to “contingent sovereignty” (erosion of non-intervention norm) underlining the role of power in US exceptionalism and thus its effects on inter-state relations thereafter. The document adopts a neorealist standpoint drawing repetitive concentration on “building a balance of power” which realist scholar Waltz interprets as formed by those states to either “establish and maintain a balance”, or for states’ “desire for universal domination” (Keohane:1986), respectful to US ambitions to take “responsibility to lead in this great mission” towards “freedom’s triumph” (NSS:2002). The NSS also indicated a Wilsonian ideological outlook sketched in the US’s “model for national success” advocating “freedom, democracy and free enterprise”.

This report will essentially be constructed by two sections: one of which will be referring to the document’s predictable accountability to the US invasion of Iraq (2003) as its historical ally; and the second, more contemporarily, US interference in the ongoing conflict in Syria as its adversary, taking the two as case studies and questioning international rule of law breaches of state-sovereignty at the hand of US preponderance missions to combat the “war against terrorists of global reach” (NSS:2002).

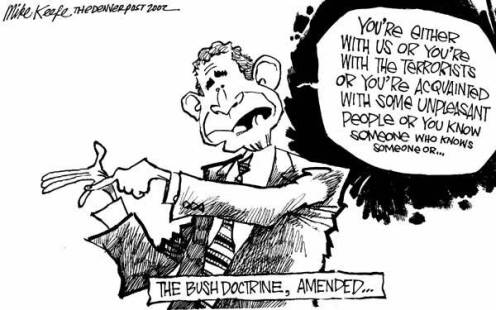

The “good vs. evil” rhetoric being US and its alliances’ cosmopolitan ‘strive’ against “tyranny, terrorism, and technology” threaded through the NSS insinuates a “with us or against us” ultimatum (Haine; Lindström:2002) in US ambitions accounting to a “means (use of military force)”, “ends (combating terror)” and “ways (combining international power)” to carry out dynamic strategic goals (Weston:2005), questionably incapable of being reached without cooperative action. This illusion of a balance of power and internationalism subject to those ‘democratic’ and multilateral alliances and institutions can be criticised as hypocritical to US unilateralism and interests.

“War occurs, for example, because a liberal state will exercise efforts to free another state from an undemocratic regime.”

The direct correlation attached to weak/‘failed’ states and terrorist activity or corruption leaves room for a hypothesised analysis, where the categorisation of a ‘failed state’ is open to interpretation. The NSS approach on this correlation portrays a logic of 9/11 terror acts as brewing a “preventive war” in the US invasion of Iraq under the Saddam regime as a self-help and ‘counter-terrorism’ agenda. This motive is thus not based on an imminent threat posed per se but as a “proactive counter-proliferation force” (NSS:2002) towards potential “suspects threatening US national security” (Reinold:2013). In this regard international legal sovereignty is placed at disregard and fundamental rights of a state’s sovereignty is challenged.

The Bush Doctrine in its use of conditional sovereignty to justify intervention in Iraq is called as an “exaggeration” of the challenges terrorist groups pose on global security (Chandler:2006) and sovereignty, and “neglects US’s violations of non-intervention norms” (Acharya:2007) which rings as “organised hypocrisy” (Krasner:1999). Acharya classes these justifications including ‘democratisation missions’ in the war on Iraq as a “façade” covering the “geopolitical and ideological basis of the invasion” (2007), indicative of the numerous controversies in US preponderance rights to “unilateral preventive and military actions” and consequently putting to question the right to state sovereignty (Tutuianu:2013). In Mearsheimer’s defence of unipolarity, he also considers that the hegemon may view its primacy as an opportunity to exercise its military power to reform the politics of a distant region (2006) as seen in the case of Iraq in the Middle East.

Further, Hehir notes motivations for the WoT were regarded as though those failed states called for “external intervention” and “democracy guidance” (2007) despite the illegality of unsolicited external interference based on principles from the UN Charter (Article 2.4) on the prohibition of intervention whereby non-intervention mirrors the sovereignty of states and a “bestowal of every state’s right to sovereignty, territorial integrity and political independence” (Oppenheim:2008). This trend in the direction of US unilateral force proves its hypocrisy bypassing UN international law and indicating changes to sovereignty whereby it is no longer bound by law but by the dominant power (monopoly on the use of force). Nonetheless Milne’s observation on the US failure to “democratise” Iraq is seen as a “transience in the unipolar moment” (2012) acting principally (or rationally) in the “pursuit of their own interests” (Krauthammer:2003).

“The choice isn’t pleasant, but at best, US interests are safeguarded.”

Challenges to international order and sovereignty remain at the forefront of political discussion and conflict initiative strategies today. The ongoing Syrian civil war under the Assad regime has undergone more strains due to continuing external interference to its already catastrophic standing within the region; where two global powers (Russia and US) take opposing positions in battles towards ‘international stability and security’. The NSS describes an emerging post-Cold War normalisation in US relations with Russia as a “cooperation in areas such as counterterrorism and missile defence” (2002) although objectives executed are not considered as such but, a “proxy war, with regional and international players arming one side or the other” (Ban Ki-moon:2012) decisive in trends of changing US-Russia relations.

Despite states as autonomous actors’ sustenance of the ability of employing sovereign jurisdiction within their defined territories (Heywood:2011), UN Security Council reformations to legally justifying foreign interference through the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) as a preventive doctrine against war crimes and crimes against humanity has been deemed as a failure in the case of the Syrian people (Adams:2015). The “duty to protect civilians” under international humanitarian law has been evidently incapable or reluctant to defend the sovereign rights of Syria by external “peace-maker” powers, together with statements from UN human rights department that all sides active may equally be committing war crimes (Shamdasani:2016), bringing to light the changing nature of state sovereignty and thus, its conditional irrelevance.

As the US and Russia are “no longer strategic adversaries” and are “building a new strategic relationship” (NSS:2002), scepticism arises in Russian officials’ criticisms against Washington’s illegitimate deployment of troops without the Syrian government’s authorisation and against the UN in condemning sovereignty violations. Nonetheless recent consensus between Russia and the US to cooperate in targeting ISIS and the al-Nusra front as the utmost goal of eradicating ISIS (particularly for US) (Gjoza:2016) implies “regional and bilateral strategies to manage change in this dynamic region” (NSS:2002). Although, the two polarised initiatives (interventionist vs. minimalist) are widely debated for a ‘peaceful’ outcome, in which Cambanis trusts a more aggressive US determination in Syria would restrict Russia’s upper hand and boost the possibility of political resolution and stability (2016). As a counter-analysis of US’s position, Gjoza views US refrainment as most ideal where continuing support of opposition forces has further led the Syrian conflict into a “bloody stalemate” and has not impacted the defeat nor prevention of ISIS and its acts of terrorism (2016). In both regards, the sovereignty of Syria is overlooked, forcing one to question whether sovereignty still exists in today’s increasingly interconnected world.

“States are rational actors and their actions are based on their desires for security, power, and wealth expansion.”

In theory, sovereignty differs from sovereignty in practice, authenticated from its changing dynamic since the Treaty of Westphalia. The 2002 NSS is an apparent documentation of this; which dedicates itself to US’s unparalleled “transformational diplomacy” in its interventionist policies (Rice:2006). In assessing becomes vital to analyse the document’s objectives and the actions exercised thereon, which I will sum up as three points. First, the Bush administration’s neocon standpoint in repetitively augmenting “democracy, freedom and peace” through necessitous intervention as its most vital concerns in combatting the WoT is a vital factor in ‘defending’ the radical shift from non-interventionism (deterrence) to an interrogation of sovereignty (pre-emption). Albeit upholding this as a means to protecting national and international security, breaches of international law and lack of consent from the international community suggests what Thucydides could see as the strong doing what they can and the weak doing what they must. Second, which relates to the former, US hypocrisies through this bring to light the debate on ‘order vs. justice’, by which abuses of justice and human rights at Guantanamo Bay can be used as an example. Third, when deliberating on the document’s use of terminologies such as the balance of power, multilateralism, alliance and cooperation, preponderant actions undertaken by the US force one to subject its policies solely to US’s own national interests, “hegemonic rivalry” and “security competition” (Wohlforth:1999). In consequence, the ‘axis of evil’ has changed; while the current Obama administration claims the WoT has come to an end, its drones continue to persevere. As ‘domino’ theorists would assert: an aggressor’s subjection of one state paves the way for its conquest in neighbouring states. It is noteworthy to summon the spread of globalisation as a major factor on the irrelevance of sovereignty today, where post-2008 formulation of emerging economies and the rise of the global ‘South’ (BRICS nations) are influencing and re-arranging the global system (unipolar to multipolar); a major challenge to US hegemony enduring economic crisis.

References

Acharya, A. “State Sovereignty After 9/11: Disorganised Hypocrisy”. Political Studies 55.2 (2007): 274-296. Web.

Adams, Simon. Failure To Protect: Syria And The UN Security Council. 1st ed. GLOBAL CENTRE FOR THE RESPONSIBILITY TO PROTECT, 2015. Web. 2 Nov. 2016.

“American Foreign Policy: Past, Present, Future”. N.p., 2010. Web. 2 Nov. 2016.

“Analyzing America’s National Security Strategy”. E-International Relations. N.p., 2016. Web. 2 Nov. 2016.

Annan, Kofi. “When Force is Considered, There is no Substitute for Legitimacy Provided by United Nations,” General Assembly Address, Sept. 13, 2002, http://www.un.org/News/Press/ docs/2002/SGSM8378.doc.htm; also See United Nations Draft Outcome Document, Sept. 13, 2005

Brahimi, Alia. “Aleppo And The Myth Of Syria’s Sovereignty”. Aljazeera.com. N.p., 2016. Web. 2 Nov. 2016.

Cambanis, Thanassis. “The Case For A More Robust U.S. Intervention In Syria”. The Century Foundation (2016): n. pag. Web.

“Chapter I | United Nations”. Un.org. N.p., 2016. Web. 2 Nov. 2016.

Elden, Stuart. “Contingent Sovereignty, Territorial Integrity And The Sanctity Of Borders”. SAIS Review 26.1 (2006): 11-24. Web.

Etzioni, Amitai. “From Right To Responsibility, The Definition Of Sovereignty Is Changing”. Insight (2006): 35. Web.

Evans, Brynn. “United States Unilateralism: Repercussions In Ally And United Nationrelations”. Web.stanford.edu. N.p., 2003. Web. 2 Nov. 2016.

Gjoza, Enea. “Let Russia Own Syria”. The National Interest. N.p., 2016. Web. 2 Nov. 2016.

Griveaud, Morgane. “Is The Anarchical International System The Cause Of War?”. E-International Relations. N.p., 2011. Web. 2 Nov. 2016.

Hehir, Aidan. “The Myth Of The Failed State And The War On Terror: A Challenge To The Conventional Wisdom”. Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 1.3 (2007): 307-332. Web.

Krauthammer, Charles. “The Unipolar Moment Revisited”. N.p., 2003. Web. 2 Nov. 2016.

Lombardo, Gabriele. “The Responsibility To Protect And The Lack Of Intervention In Syria Between The Protection Of Human Rights And Geopolitical Strategies”. The International Journal of Human Rights 19.8 (2015): 1190-1198. Web.

Mearsheimer, John. “Structural Realism”. N.p., 2006. Web. 2 Nov. 2016.

Miles, Tom. “All Sides May Be Committing War Crimes In Aleppo, U.N. Says”. Reuters. N.p., 2016. Web. 2 Nov. 2016.

Reinold, Theresa. Sovereignty And The Responsibility To Protect. London: Routledge, 2013. Print.

Sanders, Lewis. “Russia: US Deployment Violates Syria’s Sovereignty | News | DW.COM | 29.04.2016”. DW.COM. N.p., 2016. Web. 2 Nov. 2016.

“The End Of The New World Order | Seumas Milne”. the Guardian. N.p., 2012. Web. 2 Nov. 2016.

Tutuianu, Simona. Towards Global Justice: Sovereignty In An Interdependent World. T.M.C. Asser Press, 2013. Print.

United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, “Remarks to the General Assembly on Syria,” 3 August 2012, available at: http://www.un.org/sg/ statements/index.asp?nid=6224

Wood, Michael. N.p., 2007. Web. 2 Nov. 2016.

Leave a comment